Time to end PMGKAY?

PMGKAY delivered in terms of cushioning the poor and vulnerable against a large economic shock.

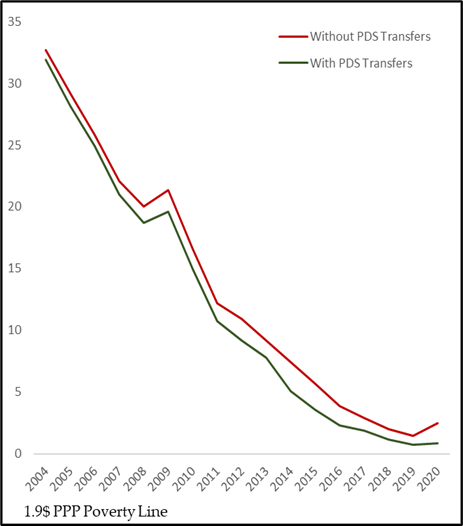

The expansion of the food subsidy program acted as insurance against several households falling into extreme poverty. We discussed this issue in our April 2022 paper ("Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from India", with Surjit S Bhalla and Arvind Virmani. IMF Working Paper No. 2022/069, April 2022.).

However, the subsidised food grains program has continued and has been extended until December 2022. It is worthwhile to ask whether there is a need for such a program in 2022 as the economy has attained the pre-pandemic levels. Some may argue that the policy should be in place and those who need it can always fall back on it to get some form of consumption support. Equally important is to recognize the opportunity cost of fiscal resources targeted towards this program at a time when the economy is appearing to have recovered in levels.

The aggregate Private Final Consumption Expenditure has been above the pre-pandemic levels for some time now. It is therefore important that we consider withdrawing the additional 5KG of wheat or rice that is provided for free. The additional 1KG of pulses under the program might still be continued due to nutritional considerations.

A more important conversation pertains to the program and whether it must be extended to 800 million people going forward. By every possible estimate, poverty in 2019 was much lower than that in 2011. Considerable uncertainty remains regarding the poverty levels in 2020 with varied estimates. However, it is undeniable that the pandemic support measures were instrumental in cushioning the impact of the pandemic even though there is some disagreement regarding the quantum of cushioning of this impact.

Nevertheless, it is about time that the Government begins unwinding the additional support extended during the pandemic. The economic rationale for the expansion of the National Food Security Act was that there was income stress so support was needed to ensure everyone had adequate food during the pandemic. The most efficient mechanism to deliver such support was through the existing programs such as the food security act and MGNREGA.

However, given that there is no stress, there is no rationale for the additional 5 KG of free wheat and rice with an additional 1KG of pulses. Given nutritional considerations, the Food Security Program can be modified to include an additional KG of pulses. However, the additional 5KG of wheat and rice must be stopped and additional fiscal resources can be diverted into other areas of the economy.

PMGKAY has so far had an estimated subsidy of Rs 3.45 lakh crore in six phases. It was supposed to serve as a temporary fiscal stimulus that would cushion the economy against the pandemic shock and be unwounded thereafter. Therefore, it is imperative that the program remains a temporary fiscal stimulus rather than becoming a permanent feature going forward.

Future of PMGKAY

A recent Finance Ministry report that looked at both the working papers on poverty that were issued in April 2022 had the following point in its recommendation. 1

“Now, it may be time to focus on further reduction in poverty based on the PPP$3.2 per capita per day through economic growth and employment generation and limit government’s cash and in-kind transfers to those whose daily incomes are lower than PPP$3.2.”

This is important as there is a question of what should be the future of PMGKAY or the food security act. The best policy intervention would be to move into cash transfers, however, that raises an important question of what happens to public procurement if it is not distributed through the PDS system.

There are few economic justifications for a public procurement system in the first place given how such implicit guarantees distort markets. Welfare to farmers or income support can be provided in a variety of ways - including cash transfers - both unconditional and conditional. In addition, there can be gap funding through transfers to help farmers recover their cost of production and earn some profits in the process. This gap funding will cover the gap between determined prices and actual prices of market transactions. Madhya Pradesh has a policy to this effect.

While there are mechanisms for smarter subsidies, self-interest and pressure groups may prevent their adoption. Therefore, assuming no changes in public procurement, there is a need to revisit the PMGKAY or the food security act.

The Finance Ministry’s report provides a useful starting point for us as it argues for reducing the coverage to only those who earn less than 3.2PPP$ per person. This should roughly corroborate to possibly India’s new extreme poverty line. Based on our estimates, roughly 45 per cent of India’s population would be covered under the Food Security Act had this criterion been used for the identification of beneficiaries in 2013.

Therefore, the act itself had substantially higher coverage than India’s poverty estimates suggested. In all fairness, it is beneficial to have coverage slightly higher than the poverty line to allow for people who are non-poor at the margin to avail of the subsidy in the event of income shocks. Based on our estimates, around 27-33 per cent of the population in 2020 are categorized as poor at the 3.2PPP$ poverty line.

The eligibility criteria for the PMGKAY (or the Food Security Act) can therefore be a poverty line that covers approximately 40 per cent of India’s population. However, for this 40 per cent, it can provide 10 KGs of subsidized food grains combined with 1 KG of pulses. Doing so will permanently increase support for the extreme poor to twice the amount compared to the pre-pandemic Food Security Act. In addition, it could provide pulses or other forms of more nutritious food.

By reducing the eligibility to receive the food subsidy, Government can direct greater support while it could potentially reduce the expenditures on the program even when compared to the pre-pandemic years. This will ultimately free up fiscal resources that must be spent on issues such as augmenting India’s social infrastructure.

Investments in India’s human capital will benefit those who are between the 40th percentile and the 80th percentile more than small food subsidies. It is therefore time to initiate a conversation about the future of the Food Security Act as the program approaches its 10th anniversary. By then, we may have a new Consumption Expenditure Survey that will be useful to guide the shape and direction of the PMGKAY - which could replace the erstwhile PDS-Food Security Act.

The report discusses the pass-through issue and while there continues to be some disagreement regarding the pass-through factors, poverty estimates with the use of a 0.92 discount factor do not change the broader results. I do, however, agree that a pass-through of 0.67 appears to be too low. The next round of the Consumption Expenditure Survey should help settle the debate on not just the prevalent poverty rates but also on the choice of pass-through factors.